Improving Shoulder Position for the Overhead Squat

The following sequence prepares the shoulders for the overhead squat, which requires motion at the shoulder blade (scapula) and arms. A stable shoulder blade position on the ribcage requires proper retraction and posterior tilt to support good arm position.

Four Elements to Establishing a Good OHS Position

#1: Finding a Comfortable Grip

#2: Lower Body Considerations

#3: Shoulder Flexion & External Rotation

#4: Scapular Stability & Mobility

#1: Finding a Comfortable Grip for the OHS & Snatch

Colin Burns, wrote a great blog for Juggernaut Training Systems discussing how grip wide effects the overhead bar position.

He explains,

“A wider grip will allow for more movement around the shoulder and a shorter distance for the bar to travel. In turn, it is a weaker position overhead, and can sometimes allow too much internal rotation at the shoulder in new lifters, leading to missing lifts forward or weakness resisting a miss backwards. This rotation is also a common compensation for a forward lean of the torso. Some people will actually start to rotate before they even begin to descend in an overhead squat.

On the flip side of the grip coin, a narrower grip will require the bar to travel further, requires a bit more mobility in the shoulder, but is stronger overhead. I find a more narrow grip is also much more resistant to the internal rotation that can be so easy to get into with a wider grip. These points among others go into finding a sweet spot that will differ from lifter to lifter.”

#2: The Lower Body Component of the Overhead Squat

Oftentimes what seems like poor shoulder flexibility is a lack of scapular stability (weak traps and serratus anterior) and/or poor lower body flexibility. The first five ‘points of performance’ of the squat lay the foundation for good arm position.

SquatRx ‘Points of Peformance’

#1: Weight on Heels

#2: Hips Below Parallel

#3: Knees Out

#4: Torso Upright

#5: Neutral Lumbar Curve

#6: Thoracic Extension

#7: Arms Overhead

In particular ankle flexibility, hip flexibility (joint-capsule, glutes, external-rotators), and good hip-flexor range of motion (quads and psoas) all affect the first five points of performance.

If you are able to sink into a deep squat and maintain the first five points of performance, then you can move on to looking at shoulder flexibility.

#3: Assessing Shoulder Flexion & External Rotation

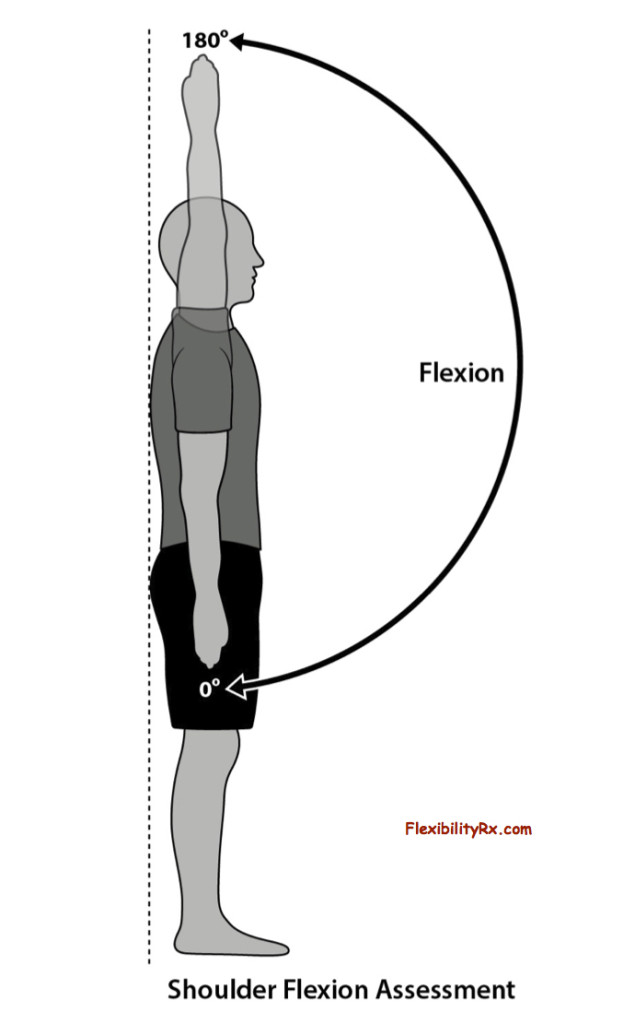

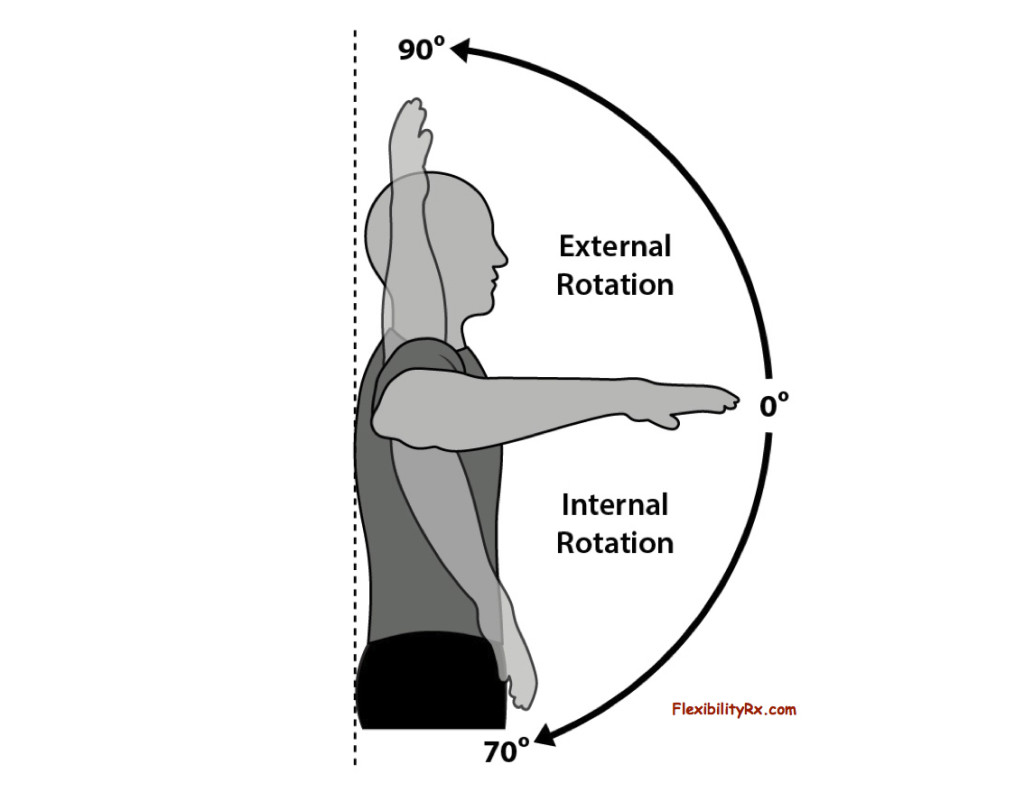

A great place to start when troubleshooting poor overhead position is an unloaded assessment of thoracic extension, shoulder flexion, and shoulder external rotation.

The starting position for both shoulder flexion and external rotation involves standing with your feet about six inches from the wall and placing your hips and spine flush against the wall. Note if your low-back is flat against the wall and if your neck is also able to easily maintain contact.

To assess shoulder flexion – slowly raise your arms overhead while keeping your low-back flat against the wall. Poor thoracic extension is a limiting factor in shoulder flexion. Note the ease with which you are able to keep your ribcage against the wall – if thoracic mobility is limited maintaining this position may be difficult.

To assess shoulder external rotation place your elbows flush against the wall, elbows bent to ninety degrees. If your palms do not lay flush against the wall your external rotation is limited.

#4: Scapular Stability & Mobility

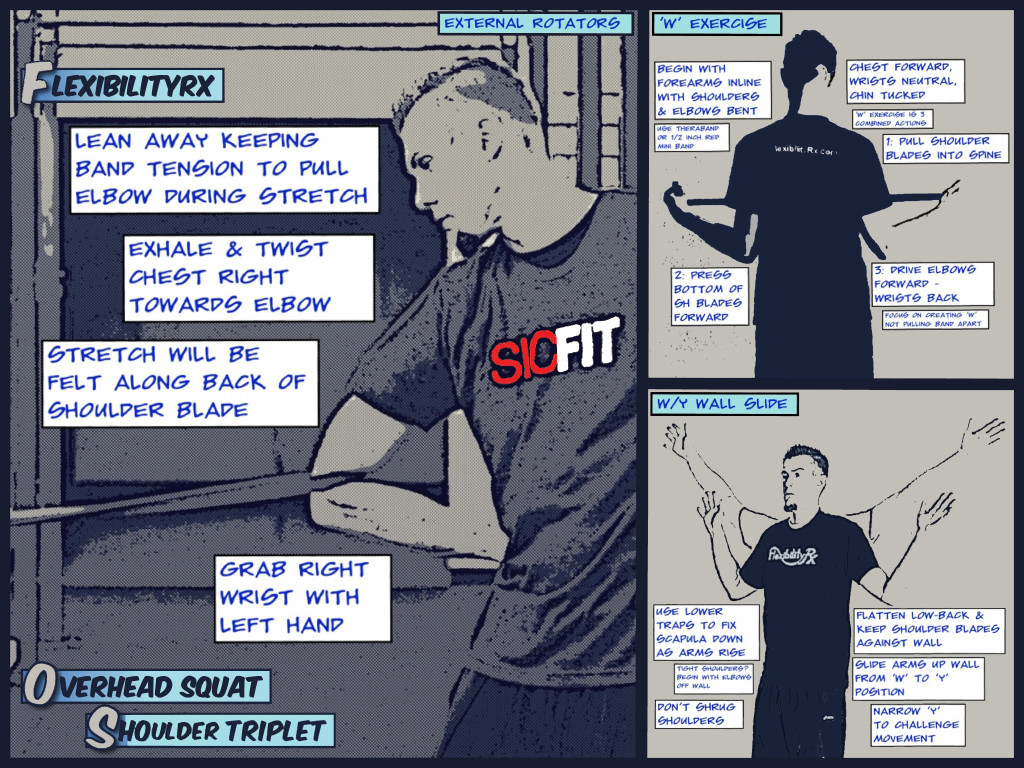

The overhead squat triplet includes two exercises for strengthening the muscles surrounding the scapula for improved stability and a stretch for the rotator cuff myofasculature (muscles and fascia).

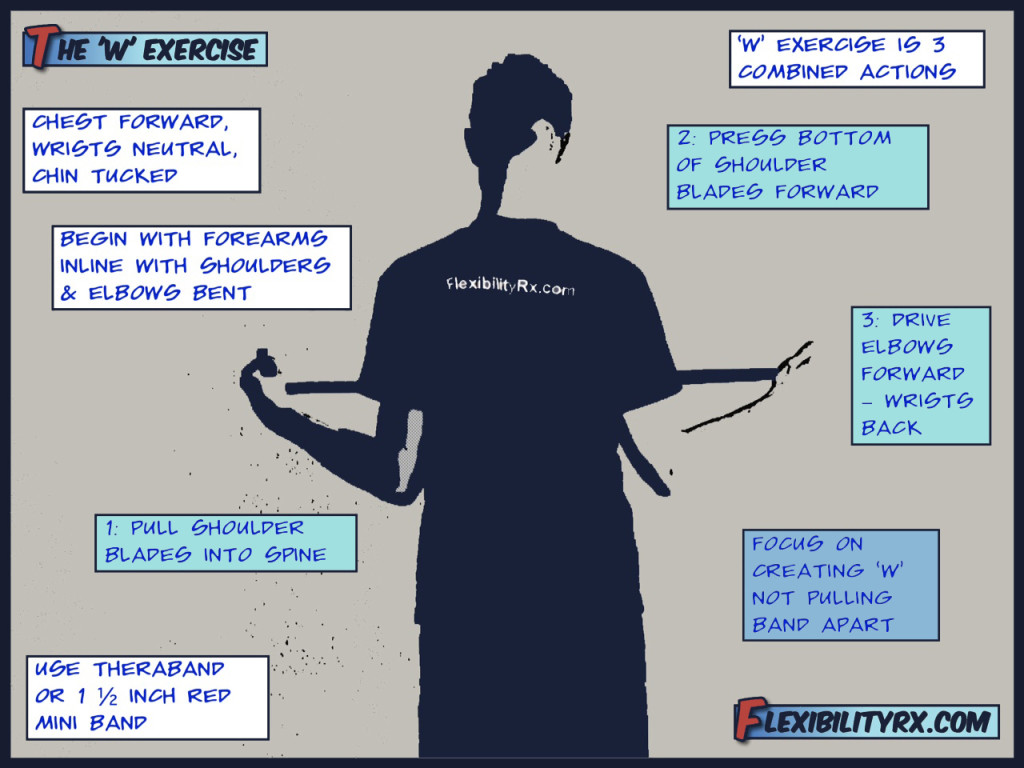

The ‘W’ Exercise – No Money Drill

The ‘W’ exercise involves a combination of three motions that place the arms in a ending position that looks like a ‘W’ from behind. This great shoulder exercise is sometimes referred to as the ‘no money’ drill because it places the arms in a, “Hey don’t look at me – I don’t have your money” position.

The ‘W’ Exercise is a combination of scapular retraction and posterior tilt as the arms externally rotate.

Instructions

The arms start out in front with the forearms parallel to the thighs – if you hold your arms out in front the elbows are bent to ninety degrees and the wrists will be inline with the knees. It is important to keep the neck neutral (chin tucked) and maintain thoracic extension (chest forward). As you perform the three combined motions (see instructions 1-3) the forearms will move out to the sides (external rotation) as the scapular posteriorly tilts and retracts.

Scapular Retraction & Posterior Tilt

Retraction involves drawing the scapula in towards the spine. Posterior tilt sets the scapula flat on the ribcage. If you round your shoulders forward you can feel the bottom part of the shoulder blade stick out away from the ribcage (winging) as it anteriorly tilts into a bad position. If you visualize the scapula as an upside down triangle, posterior tilt involves driving the bottom ‘pointy’ part forward so it lays flat on the ribcage.

The graphic below shows good retraction and posterior tilt of the scapula – as the shoulder blade rests flush against the ribcage. The illustration on the right shows an anteriorly tilted shoulder blade that is also restricting shoulder flexion.

External Rotation of the Arms

External rotation in this position involves moving the forearms out to the side. It is important to not try to pull the band apart, but to drive the movement from the shoulder blade in coordination with the external rotation of the arms. Good external rotation of the shoulders is important for pressing overhead and the overhead squat.

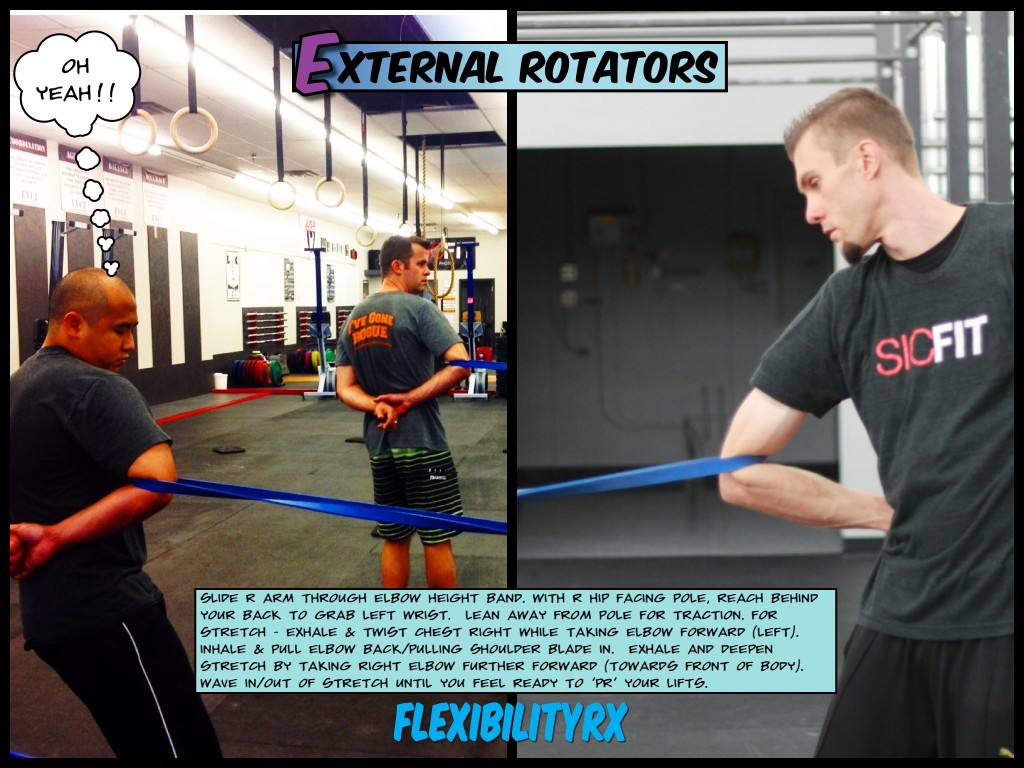

Rotator Cuff Stretch

The external-rotator stretch releases the external rotators, which often ‘bind’ the shoulder blade to the arms. The arm needs to be able to move independently of the shoulder blade which is not possible if the external rotators (infraspinatus, teres minor) are ‘stuck’ and limiting the motion of the arms. The rotator cuff stretch applies traction to the shoulder joint-capsule and releases the fascia of the rotator cuff.

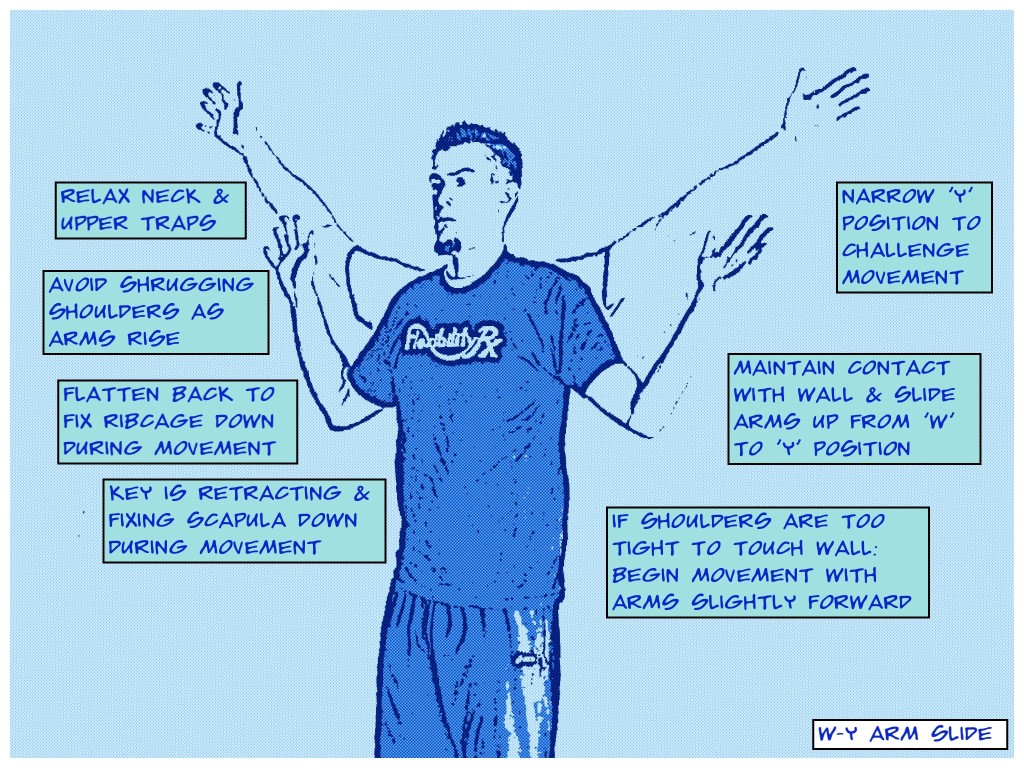

W/Y Wall Slide Exercise

Lastly the W/Y wall slide trains arm movement with the shoulder blade stabilized, which is needed for the overhead squat.

“The key to the Wall Slide (W/Y) is that the shoulder blades remain retracted and depressed while the gleno-humeral joint attempts to move the arms overhead. They are the “air guitar” of overhead pressing. Many beginners will actually cramp in the lower trap/ rhomboid area as they attempt this exercise. The key is that the forearms must slide up in contact with the wall while the shoulder blades stay down and back.” – Mike Boyle

– Kevin Kula, “The Flexibility Coach” – Creator of FlexibilityRx™

Related Resources

JTS Strength: FIXING THE SNATCH AND OVERHEAD SQUAT POSITION (link)

Breaking Muscle: Smartest Progression for Building Your Overhead Lifts (link)

Mike Boyle: Advances in Functional Training

Mike Reinold: The Shoulder W Exercise (link)

Tony Gentilcore: EXERCISES YOU SHOULD BE DOING: BAND NO-MONEY DRILL (link)

Tags: overhead squat position, scapular stability, shoulder mobility

Leave A Reply (No comments so far)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No comments yet